Born in British-occupied Egypt, Huda Shaarawi was an activist, philanthropist, and trailblazing feminist. She was both an integral member of the Wafd party and the founder of the first women's organizations in Egypt. Her contributions to the struggle for Egyptian independence won her the highest award given by the Egyptian government, but she was never allowed to vote or participate in the government she fought for.

Nur al-Huda Sultan was born on the family estate of Al-Minya near Cairo on June 23, 1879. Her father, Muhammed Sultan Pasha, was an important official in the colonial government, and at the time of Huda's birth he was serving as the inspector general of Upper Egypt. A wealthy man, he had both a wife, Hasiba, and several concubines. Huda's mother, Iqbal Hanim, was one of these concubines.

Iqbal was much younger than her not-quite-husband. She was Circassian, and had been raised in Istanbul after her family fled expansionist Russians in the Caucasus. She was sent to Egypt to live with her uncle after one of her sisters was abducted while resettling in the Ottoman capital. She ended up as a concubine to Muhammed, who was several years her senior, and she had Huda when she was just 19 years old.

In her memoir, The Harem Years, Huda described her mother as being difficult to know but her father as being warm and loving, though he was frequently away on government business. She described him as being a kind and attentive father, who always had a sweet and a moment for his children.

Though he may have been a good father, Muhammed wasn't very good at his job, and fought frequently with Khedive Ismail, to the point where he was briefly exiled to Sudan. He was accused by many of having abetted Khedive Tewfik Pasha and of helping the British Empire reduce Egypt to a suzerainty, an accusation that Huda bitterly resented, saying in her memoirs:

Another important figure in Huda's childhood was her father's wife, Hasiba. Huda referred to her as Umm Kabira, or "big mother," and enjoyed a closer relationship with Hasiba than she did with her own mother. Huda always felt that she was playing second fiddle to her brother, and Hasiba listened when Huda vented her jealousy and frustration over the preferential treatment her brother received. Huda would often spend days with Hasiba, and it was Hasiba who first explained to Huda that boys were far more valued in Egyptian society.

In 1884, Huda's father died of a kidney disease while abroad in Graz, Austria. He had gone to Switzerland to seek medical help and had been on his way home to Egypt when he died unexpectedly on August 14 at The Elephant Hotel. His death devastated the family, throwing Huda's mother and Hasiba into a deep depression. Both women would lie in bed for days, sending Huda and her younger brother, Umar, away.

Huda had a complicated relationship with her brother because while she loved him dearly, she was also jealous of the attention he received. Umar was sickly and absorbed the lion's share of Iqbal's attention, even when well. In her memoirs, Huda recalled wanting to be sick herself so she would receive similar love and care. She fell sick with a fever and spent a day receiving all the love and care she could possibly wish for. However, when her brother fell sick the next day, her mother and the doctors more or less forgot about her, despite her worsening condition. Huda recovered, but she was never close to her mother again. Though she was never close to her mother, Huda enjoyed a very close relationship with her brother, sharing the same lessons and games with him throughout their childhood. Huda assumed a motherly role with her brother, and when Umar's nursemaid and the eunuchs who watched over him encouraged him to neglect his schooling, Huda ensured that he studied.

Education and learning was a lifelong passion of Huda's. She received the typical education for a young woman of her class, but Huda was eager to learn more beyond that, however, specifically wanting to learn to read Arabic so she could study the Koran herself. Early attempts to learn Arabic grammar were foiled by the eunuchs of her family's harem who forbade her from learning it because she wouldn't be a judge. This made Huda keenly aware of the difference in education available to girls and boys, a difference that she would spend her life struggling to correct for herself and others.

At age nine, Huda finished memorizing the Koran, a remarkable and unusual achievement. However, she was unable to read, so she began to study Turkish, learning to read, write, and speak. She studied Turkish and Persian poetry, as well as calligraphy in both of the Ottoman scripts. She learned French and piano and began buying books from the peddlers who came to her door. Huda was not encouraged to read, and she was forbidden to buy books, but she did so nonetheless and began to sneak books out of her father's library. She loved poetry and wanted desperately to learn to write poetry herself but was held back by her lack of knowledge.

One of the largest figures of inspiration in Huda's early years was the poet Sayyida Khadija. Sayyida would often come and stay with Huda and her family, and Huda was impressed with how Sayyida could converse freely with men, and meet them on the same level intellectually. Sayyida's example made Huda even more adamant that education was necessary for women to be equal to men.

When she hit puberty, Huda was consigned to the harem to while away the time until she was married off. Huda was less than pleased. She was even less pleased about having to veil when she left home. Veiling as well as keeping women in a harem was a standard practice of the upper classes and more affluent middle classes in Egypt at that time. Forcing women to veil and keeping them in seclusion was a sign of status and wealth--not, as many historians, journalists, and casual racists like to suggest, a draconian tenant of Islam. Egyptian veiling and seclusion was considered odd and impractical by the other Arab countries at the time.

Huda certainly agreed that it was impractical, and she resented being separated at age eleven from all of her childhood friends, many of whom were the same little boys that her brother played with as well.

When Huda was twelve, she was betrothed to her much older cousin Ali Shaarawi, the man who had been appointed legal guardian over her and her brother after her father's death. Neither Huda nor her mother were very pleased about this match. Iqbal was leery of marrying Huda off to a man significantly her senior. The fact that Ali, who was in his 40s, had illegitimate children who were much older than Huda didn't do anything to ease their minds.

However, Huda's mother was evidently unable to do anything to prevent the match and instead negotiated an extremely strict marriage contract. The contract stipulated complete monogamy; Ali would have to give up his concubines and live only with Huda. The entire marriage was negotiated in utmost secrecy, and Huda herself was not aware of her impending nuptials until it came time to sign the marriage contract.

Huda was distraught. She had always regarded Ali as a father or an older brother, and she had no desire to marry him. She had been put off by his cold demeanor and open favoritism of her brother. However, she was unable to prevent the marriage, and in 1891, she wed Ali Shaarawi.

Luckily for Huda, Ali was unable to keep his sausage in his trousers, and a little over a year after they married, he had sired another child with the same slave-concubine who had borne his previous children, in violation of the marriage contract. Delighted, Huda returned to her mother's house and took up the threads of her old life. Despite Ali's attempts to reconcile with her, Huda would spend the next seven years on her own.

Huda spent those seven years furthering her education, learning drawing and painting, perfecting her French and teaching herself Arabic grammar. She loved music, frequently went to the opera and, on returning home, would play the pieces sung on stage on the piano from memory. Huda formed close friendships with several women, both Egyptian and foreign, and it was one of these women, Eugenie Le Brun, who ignited the fire of Huda's activism.

Eugenie Le Brun had been born in France, but emigrated to Egypt after meeting and marrying her husband, Hussein Roshdy Pasha, who would later be the prime minister of Egypt. Eugenie had traveled with Hussein to Cairo and converted to Islam. She was a popular hostess and introduced Huda into Cairo society. Eugenie would help Huda with her French, and frequently suggested books for Huda to read. She also convinced Huda to join her women-only salon.

Turn-of-the-century Egypt didn't encourage much social mixing between men and women. Many of the salons started by European women of the era were co-ed and therefore attracted few to no native Egyptian women. Eugenie's salon was the first female-only salon and the only one Huda would attend. They discussed social issues, like veiling and the status of women in Egyptian society, as well as more pedestrian topics such as children and immorality.

Eugenie was a writer and wrote multiple books to educate Europeans about the status and position of women in Egypt. She shared her writing with Huda, and Huda credited her as being an inspiration and guide throughout her life, even after Eugenie's death in 1908.

There were several attempts to reconcile Huda with her husband. Numerous family friends and relatives, along with Ali himself, would frequently confront Huda to try and convince her to return to life with Ali. However, it wasn't until Umar confided in Huda that he wouldn't marry until she was reconciled with her husband that Huda relented.

Though Huda gave few details about how their reconciliation went, it seems to have not gone terribly because she and Ali had two children--Bathna and Muhammad--together in 1903 and 1905. At about 10 months, Bathna contracted an unknown illness, nearly dying multiple times. Bathna didn't recover, and doctors suggested that she be taken abroad to Europe for better air. Ali was reluctant to let his daughter leave Egypt, but Huda threatened to leave him if he didn't allow her to take Bathna abroad. Ali relented, and Huda took Bathna to Turkey. They spent three months in Istanbul, but Bathna did not recover. Huda withdrew from everyone, much to the consternation of her friends and husband. It wasn't until Bathna was diagnosed with malnutrition in 1908 that she got better, and Huda returned to society.

In 1909 Huda met Marguerite Clement, a Luxembourgish feminist and public speaker. She was on a lecture tour of Eastern countries, and after a night at the opera, she and Huda decided that she should give a lecture to Egyptian women.

A public lecture just for women was unprecedented in Egypt. While women socialized, they did not do so in public spaces, and they certainly didn't gather in large numbers. Holding a public meeting for women was met with some skepticism, but after Princess Ayn al-Hayat promised to sponsor the lecture, there wasn't much any skeptic could do to stop it. On Ali's advice, Huda booked the lecture hall for Friday at the local university. The lecture was a smashing success, and on Prince, later King, Ahmed Fuad, ordered that the hall be booked for every Friday into perpetuity.

These lectures were the beginning of a movement for education for women in Egypt. As more and more lectures were held, and as more Egyptian women were giving lectures Huda decided it was necessary to make that thing official. In April of 1914, she founded the Intellectual Association of Egyptian Women, a group of upper-class women dedicated to providing intellectual activities for Egyptian women.

Fast forward to 1919. The dust of the first world war was starting to settle, and things were restive in Egypt. The fledgling League of Nations was redrawing international boundaries, and Egypt was starting to wonder if it was maybe going to finally become free of the British.

However, the British were reluctant to part with their colonial possessions, and since Britain had been on the winning side of WWI, no one was forcing them to give up Egypt. Native Egyptians, however, weren't having it, and after their representatives to negotiate with the British were exiled to the Seychelles (a favorite move on the part of the British), they formed the Wafd party to fight the British for real.

Meanwhile, Huda's marriage to Ali was on the rocks. Ali had requested the hand of Huda's 14-year-old niece for his natural son Hasan, and Huda didn't like the idea. Hasan hadn't finished his education and was in no position to be supporting a wife and family. Huda's disapproval caused a rift between Huda and Ali that, according to Huda, would have ended in separation if not for the nationalist movement.

The Wafd party was founded in November of 1918 with Saad Zaghloul as president and Ali as treasurer. Their first goal was to speak with the British Home Office in London, and to attend the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. They were initially denied permission for either. They did eventually make it to the peace conference, but it was only to hear the US President, Woodrow Wilson, endorse the British occupation of Egypt, an endorsement that put paid to any hope the Egyptians had of foreign intervention.

Throughout this, Huda was working behind the scenes, playing a diplomat between her husband, other members of the Wafd, and British officials. When Wafd leaders started being imprisoned and deported, Ali became de facto leader. He took Huda into his confidence, telling her all the Wafd secrets and plans so that, should he be arrested, she could lead the Wafd.

In order to further Wafd aims, Huda formed the Wafdist Women's Central Committee, (WWCC) an organization made up of Egyptian women of all classes working towards Egyptian independence. Public gatherings were banned by the British, so the Wafd women held large "social gatherings" in the harem of Huda's home, where they composed formal letters to the British, voted to end the protectorate, and, most importantly, organized the March 16, 1919 protests and the boycott of British goods.

After the arrest and deportation of Saad Zaghoul in March of 1919, mass strikes and protests spread through Cairo. Law students, shouting nationalist slogans and calling for Saad's return marched through the streets. In support, the Wafd organized a general strike of government employees. In order to enforce the strike, Huda and other women would stand in the doorways of the homes of government workers, and refuse to move. They would pay them off with jewelry so they could feed their families.

However, fighting scabs wasn't Huda's main goal. On March 16, 1919, the women of Cairo, riding in carts and carriages, organized a mass protest. They were shot at and physically assaulted as they marched through the streets until they were surrounded by British soldiers and Egyptian police outside the parliament building. For hours they stood in the sun, withstanding cruel invectives and attempts to remove them. They were widely applauded by the students who had protested just a few days prior, and though they were unable to complete their planned march, they sent a clear sign to the British that Egyptian women weren't going to back down.

The crowning glory of Huda's nationalist action was the 1922 boycott against British goods and banks. Under Islamic law, women had access to their own money and inheritance, and as the main purchasers of the house, women held significant economic power. The sudden withdrawal of money from British banks and the mass departures of customers from British merchants hit the British hard, making Egypt a much less satisfying economic possession. Meanwhile, the new Egyptian bank received significant business, and Egyptian vendors were suddenly very prosperous. The boycott was lauded by the male Wafdists as an integral part of their movement.

During the boycott, Ali died. Huda however, carried on, saying that

Egyptians were granted nominal independence by the end of 1922, and were allowed to form their own government, with a lot of help from the British. In April of 1923, the new government drafted a constitution. At first blush, it seemed promising, emphasizing that all Egyptians were equal before the law, regardless of race, religion, or language. However, when the constitution passed, it became clear that women were not equal before the law. The status of women in Egypt hadn't changed, and only men were allowed the vote.

Huda was furious. After protesting, being shot at, and heading an instrumental boycott, she and the other women who had been an integral part of the movement were barred from participating in government.

In April of 1923, Huda founded the Egyptian Feminist Union. The union was founded on the idea that in Ancient Egypt ,men and women had been equal, with equal rights to education and property. This equality had been lost through imperialism and misinterpretations of the Koran. The Egyptian Feminist Union aimed to restore that equality.

Unlike many Western feminist unions of the time, the Egyptian Feminist Union focused mainly on social issues, not just on suffrage. The goal of the Egyptian Feminist Union was to put in place better protections of women and girls under the law, namely:

It was while returning from an international women's conference in Rome that one of the most lauded and mythologized incidents of Huda's life occurred. In May of 1923, after returning from a conference in Rome, Huda boldly removed her face veil in a train station, signaling that she would no longer adhere to the repressive rules of men.

The Wafd took control of parliament at the end of 1923. At the inauguration of parliament, the only women allowed to attend were the wives of ministers. It became clear that women would be barred from participating in the Wafd government, just as they had been barred from participating in the previous government, so Huda arranged a protest for the day of the opening of Parliament. Members of the Women's Wafdist Central Committee and the Egyptian Feminist Union picketed the parliament building. They sent a list of demands to the new government, but their demands fell on deaf ears.

Wafdist men continued to ignore Wafdist women, and this eventually led to Huda stepping down from the WWCC after, contrary to WWC wishes, the Wafdist men capitulated to British demands over Sudan. Huda called for Prime Minister Zaghloul's resignation in an open letter in the newspaper after she found herself being pushed out of the party because she and the WWCC refused to tow the party line.

While that was the end of Huda's association with the Wafd, it was, by no means, the end of Huda's nationalist activism. However, her further nationalist activism was usually done within a feminist framework.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Huda started to turn her feminist work outwards, as she began framing feminism as not just an Egyptian issue but also a pan-Arab issue. In 1944, she helped found the Arab Feminist Union, but even before that, she worked to help feminist movements throughout the Middle East. When Palestinian feminists requested her help in 1943 she raised funds, and ended up starting the conference that would lead to the formation of the Arab Feminist Union.

Part of the reason Huda was so invested in framing feminism within a pan-Arab framework was because it was becoming rapidly clear that no real help was going to come from feminists in Europe, the United States, and Canada. While Western feminists meant well, and many certainly thought they were doing good, they looked down on Arab women, and failed to understand the differences between Arab and Western culture. White feminists viewed themselves as superior to Middle Eastern feminists because they were white, and colonial attitudes were still a prevalent feature at international feminist conferences. European feminists couldn't understand the struggle that Huda and other Middle Eastern feminists faced and therefore weren't reliable allies. Because she couldn't rely on the existing feminist organization's, Huda created her own.

Huda spent the latter years of her life lobbying and organizing. In the 1930s, her work started to focus on the rights of women workers and on ensuring that women were treated equally in the workplace. There were many instances when women workers came to Huda seeking help, and she dealt directly with the Egyptian Labor Board to resolve the issue.

In 1945, she was awarded the Nishan al-Karmal award, Egypt's feminine equivalent of a knighthood. She was, however, still unable to vote. She died two years later on August 12th.

Huda started the feminist movement in Egypt, and through her dogged work and determination, she was able to drastically improve the situation for women in Egypt. Though change was sometimes slow and incremental (the harem system would not be fully dismantled until after her death), she was able to put in place the infrastructure that would ensure that the next generation of Egyptian feminists was able to continue the fight after she was gone.

This article was edited by Mara Kellogg.

Sources

The Harem Years by Huda al-Shaarawi

"Early Twentieth-Century Middle Eastern Feminisms, Nationalisms, and Transnationalisms" by Mary Ann Fay

"Challenging Imperialism in International Women's Organizations, 1888-1945" by Leila J. Rupp

"Between Nationalism and Feminism: The Eastern Women's Congresses of 1930 and 1932" by Charlotte Webber

Huda Sharawi-Britannica

Huda Shaarawi-Encyclopedia

Shaarawi, Huda-Melissa Spatz

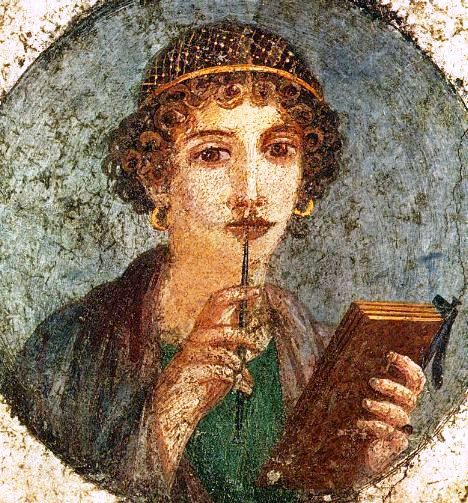

|

| Huda SHaarawi-1900 |

Iqbal was much younger than her not-quite-husband. She was Circassian, and had been raised in Istanbul after her family fled expansionist Russians in the Caucasus. She was sent to Egypt to live with her uncle after one of her sisters was abducted while resettling in the Ottoman capital. She ended up as a concubine to Muhammed, who was several years her senior, and she had Huda when she was just 19 years old.

In her memoir, The Harem Years, Huda described her mother as being difficult to know but her father as being warm and loving, though he was frequently away on government business. She described him as being a kind and attentive father, who always had a sweet and a moment for his children.

Though he may have been a good father, Muhammed wasn't very good at his job, and fought frequently with Khedive Ismail, to the point where he was briefly exiled to Sudan. He was accused by many of having abetted Khedive Tewfik Pasha and of helping the British Empire reduce Egypt to a suzerainty, an accusation that Huda bitterly resented, saying in her memoirs:

"My father has been maligned by certain so-called patriots, distorters of history"Huda used her memoir, The Harem Years, to make the case for her father's fidelity to his homeland. She credited the accusations, along with the loss of her half brother, for shortening her father's life.

Another important figure in Huda's childhood was her father's wife, Hasiba. Huda referred to her as Umm Kabira, or "big mother," and enjoyed a closer relationship with Hasiba than she did with her own mother. Huda always felt that she was playing second fiddle to her brother, and Hasiba listened when Huda vented her jealousy and frustration over the preferential treatment her brother received. Huda would often spend days with Hasiba, and it was Hasiba who first explained to Huda that boys were far more valued in Egyptian society.

|

| Huda |

Huda had a complicated relationship with her brother because while she loved him dearly, she was also jealous of the attention he received. Umar was sickly and absorbed the lion's share of Iqbal's attention, even when well. In her memoirs, Huda recalled wanting to be sick herself so she would receive similar love and care. She fell sick with a fever and spent a day receiving all the love and care she could possibly wish for. However, when her brother fell sick the next day, her mother and the doctors more or less forgot about her, despite her worsening condition. Huda recovered, but she was never close to her mother again. Though she was never close to her mother, Huda enjoyed a very close relationship with her brother, sharing the same lessons and games with him throughout their childhood. Huda assumed a motherly role with her brother, and when Umar's nursemaid and the eunuchs who watched over him encouraged him to neglect his schooling, Huda ensured that he studied.

Education and learning was a lifelong passion of Huda's. She received the typical education for a young woman of her class, but Huda was eager to learn more beyond that, however, specifically wanting to learn to read Arabic so she could study the Koran herself. Early attempts to learn Arabic grammar were foiled by the eunuchs of her family's harem who forbade her from learning it because she wouldn't be a judge. This made Huda keenly aware of the difference in education available to girls and boys, a difference that she would spend her life struggling to correct for herself and others.

At age nine, Huda finished memorizing the Koran, a remarkable and unusual achievement. However, she was unable to read, so she began to study Turkish, learning to read, write, and speak. She studied Turkish and Persian poetry, as well as calligraphy in both of the Ottoman scripts. She learned French and piano and began buying books from the peddlers who came to her door. Huda was not encouraged to read, and she was forbidden to buy books, but she did so nonetheless and began to sneak books out of her father's library. She loved poetry and wanted desperately to learn to write poetry herself but was held back by her lack of knowledge.

One of the largest figures of inspiration in Huda's early years was the poet Sayyida Khadija. Sayyida would often come and stay with Huda and her family, and Huda was impressed with how Sayyida could converse freely with men, and meet them on the same level intellectually. Sayyida's example made Huda even more adamant that education was necessary for women to be equal to men.

|

| A Cairo mashrabiya. Mashrabiya were a frequent architectural feature of harems, as they allowed women to look out onto the street, but not be observed. |

Huda certainly agreed that it was impractical, and she resented being separated at age eleven from all of her childhood friends, many of whom were the same little boys that her brother played with as well.

When Huda was twelve, she was betrothed to her much older cousin Ali Shaarawi, the man who had been appointed legal guardian over her and her brother after her father's death. Neither Huda nor her mother were very pleased about this match. Iqbal was leery of marrying Huda off to a man significantly her senior. The fact that Ali, who was in his 40s, had illegitimate children who were much older than Huda didn't do anything to ease their minds.

However, Huda's mother was evidently unable to do anything to prevent the match and instead negotiated an extremely strict marriage contract. The contract stipulated complete monogamy; Ali would have to give up his concubines and live only with Huda. The entire marriage was negotiated in utmost secrecy, and Huda herself was not aware of her impending nuptials until it came time to sign the marriage contract.

Huda was distraught. She had always regarded Ali as a father or an older brother, and she had no desire to marry him. She had been put off by his cold demeanor and open favoritism of her brother. However, she was unable to prevent the marriage, and in 1891, she wed Ali Shaarawi.

Luckily for Huda, Ali was unable to keep his sausage in his trousers, and a little over a year after they married, he had sired another child with the same slave-concubine who had borne his previous children, in violation of the marriage contract. Delighted, Huda returned to her mother's house and took up the threads of her old life. Despite Ali's attempts to reconcile with her, Huda would spend the next seven years on her own.

Huda spent those seven years furthering her education, learning drawing and painting, perfecting her French and teaching herself Arabic grammar. She loved music, frequently went to the opera and, on returning home, would play the pieces sung on stage on the piano from memory. Huda formed close friendships with several women, both Egyptian and foreign, and it was one of these women, Eugenie Le Brun, who ignited the fire of Huda's activism.

|

| Eugenie le Brun |

Turn-of-the-century Egypt didn't encourage much social mixing between men and women. Many of the salons started by European women of the era were co-ed and therefore attracted few to no native Egyptian women. Eugenie's salon was the first female-only salon and the only one Huda would attend. They discussed social issues, like veiling and the status of women in Egyptian society, as well as more pedestrian topics such as children and immorality.

Eugenie was a writer and wrote multiple books to educate Europeans about the status and position of women in Egypt. She shared her writing with Huda, and Huda credited her as being an inspiration and guide throughout her life, even after Eugenie's death in 1908.

There were several attempts to reconcile Huda with her husband. Numerous family friends and relatives, along with Ali himself, would frequently confront Huda to try and convince her to return to life with Ali. However, it wasn't until Umar confided in Huda that he wouldn't marry until she was reconciled with her husband that Huda relented.

Though Huda gave few details about how their reconciliation went, it seems to have not gone terribly because she and Ali had two children--Bathna and Muhammad--together in 1903 and 1905. At about 10 months, Bathna contracted an unknown illness, nearly dying multiple times. Bathna didn't recover, and doctors suggested that she be taken abroad to Europe for better air. Ali was reluctant to let his daughter leave Egypt, but Huda threatened to leave him if he didn't allow her to take Bathna abroad. Ali relented, and Huda took Bathna to Turkey. They spent three months in Istanbul, but Bathna did not recover. Huda withdrew from everyone, much to the consternation of her friends and husband. It wasn't until Bathna was diagnosed with malnutrition in 1908 that she got better, and Huda returned to society.

In 1909 Huda met Marguerite Clement, a Luxembourgish feminist and public speaker. She was on a lecture tour of Eastern countries, and after a night at the opera, she and Huda decided that she should give a lecture to Egyptian women.

| Marguerite Clements |

These lectures were the beginning of a movement for education for women in Egypt. As more and more lectures were held, and as more Egyptian women were giving lectures Huda decided it was necessary to make that thing official. In April of 1914, she founded the Intellectual Association of Egyptian Women, a group of upper-class women dedicated to providing intellectual activities for Egyptian women.

Fast forward to 1919. The dust of the first world war was starting to settle, and things were restive in Egypt. The fledgling League of Nations was redrawing international boundaries, and Egypt was starting to wonder if it was maybe going to finally become free of the British.

However, the British were reluctant to part with their colonial possessions, and since Britain had been on the winning side of WWI, no one was forcing them to give up Egypt. Native Egyptians, however, weren't having it, and after their representatives to negotiate with the British were exiled to the Seychelles (a favorite move on the part of the British), they formed the Wafd party to fight the British for real.

Meanwhile, Huda's marriage to Ali was on the rocks. Ali had requested the hand of Huda's 14-year-old niece for his natural son Hasan, and Huda didn't like the idea. Hasan hadn't finished his education and was in no position to be supporting a wife and family. Huda's disapproval caused a rift between Huda and Ali that, according to Huda, would have ended in separation if not for the nationalist movement.

The Wafd party was founded in November of 1918 with Saad Zaghloul as president and Ali as treasurer. Their first goal was to speak with the British Home Office in London, and to attend the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. They were initially denied permission for either. They did eventually make it to the peace conference, but it was only to hear the US President, Woodrow Wilson, endorse the British occupation of Egypt, an endorsement that put paid to any hope the Egyptians had of foreign intervention.

Throughout this, Huda was working behind the scenes, playing a diplomat between her husband, other members of the Wafd, and British officials. When Wafd leaders started being imprisoned and deported, Ali became de facto leader. He took Huda into his confidence, telling her all the Wafd secrets and plans so that, should he be arrested, she could lead the Wafd.

In order to further Wafd aims, Huda formed the Wafdist Women's Central Committee, (WWCC) an organization made up of Egyptian women of all classes working towards Egyptian independence. Public gatherings were banned by the British, so the Wafd women held large "social gatherings" in the harem of Huda's home, where they composed formal letters to the British, voted to end the protectorate, and, most importantly, organized the March 16, 1919 protests and the boycott of British goods.

After the arrest and deportation of Saad Zaghoul in March of 1919, mass strikes and protests spread through Cairo. Law students, shouting nationalist slogans and calling for Saad's return marched through the streets. In support, the Wafd organized a general strike of government employees. In order to enforce the strike, Huda and other women would stand in the doorways of the homes of government workers, and refuse to move. They would pay them off with jewelry so they could feed their families.

|

| Women protesting in Cairo |

The crowning glory of Huda's nationalist action was the 1922 boycott against British goods and banks. Under Islamic law, women had access to their own money and inheritance, and as the main purchasers of the house, women held significant economic power. The sudden withdrawal of money from British banks and the mass departures of customers from British merchants hit the British hard, making Egypt a much less satisfying economic possession. Meanwhile, the new Egyptian bank received significant business, and Egyptian vendors were suddenly very prosperous. The boycott was lauded by the male Wafdists as an integral part of their movement.

During the boycott, Ali died. Huda however, carried on, saying that

"Neither illness, grief, nor fear of censure can prevent me from shouldering my duty with you in the continuing fight for our national rights. I have vowed to you and to myself to struggle until the end of my life to rescue our beloved country from occupation and oppression...Neither repeated hardships, nor the heavy handedness of our present government will lessen my will nor deter me from fighting for the full independence of my country."Unfortunately, those same men who applauded Huda and her sisters as being essential to Egyptian independence failed to include them in negotiations with the British. Huda and the other members of the WWCC expected that they would be equal to the men when it came to negotiations with the British, and in the Egyptian republic to come. They sent some sharply worded letters to their male counter parts, and the men sheepishly relented. While equality between the male and female Wafdists seemed to have been restored, this was a dark foreshadowing of what was to come.

Egyptians were granted nominal independence by the end of 1922, and were allowed to form their own government, with a lot of help from the British. In April of 1923, the new government drafted a constitution. At first blush, it seemed promising, emphasizing that all Egyptians were equal before the law, regardless of race, religion, or language. However, when the constitution passed, it became clear that women were not equal before the law. The status of women in Egypt hadn't changed, and only men were allowed the vote.

Huda was furious. After protesting, being shot at, and heading an instrumental boycott, she and the other women who had been an integral part of the movement were barred from participating in government.

|

| Huda (center) at the International Feminist Meeting in Rome, 1923 |

Unlike many Western feminist unions of the time, the Egyptian Feminist Union focused mainly on social issues, not just on suffrage. The goal of the Egyptian Feminist Union was to put in place better protections of women and girls under the law, namely:

- A reformation of personal status laws

- Raising the minimum age of marriage

- The end of polygamy

- The end of easy access for men to divorce their wives

- Women to have equal rights of inheritance as their brothers

- Women to have custody of their children in the event of a divorce

- Equal access to education for women.

At its height, the Egyptian Feminist Union had 250 members from the upper and middle classes. During Huda's time they were successful in raising the minimum age of marriage and in establishing the first secondary school for girls. They put out two journals, and provided clinics and dispensaries to poor women. They provided vocational training for women and girls. They continue fighting for the equality of women and girls in Egypt to this day.

It was while returning from an international women's conference in Rome that one of the most lauded and mythologized incidents of Huda's life occurred. In May of 1923, after returning from a conference in Rome, Huda boldly removed her face veil in a train station, signaling that she would no longer adhere to the repressive rules of men.

The Wafd took control of parliament at the end of 1923. At the inauguration of parliament, the only women allowed to attend were the wives of ministers. It became clear that women would be barred from participating in the Wafd government, just as they had been barred from participating in the previous government, so Huda arranged a protest for the day of the opening of Parliament. Members of the Women's Wafdist Central Committee and the Egyptian Feminist Union picketed the parliament building. They sent a list of demands to the new government, but their demands fell on deaf ears.

Wafdist men continued to ignore Wafdist women, and this eventually led to Huda stepping down from the WWCC after, contrary to WWC wishes, the Wafdist men capitulated to British demands over Sudan. Huda called for Prime Minister Zaghloul's resignation in an open letter in the newspaper after she found herself being pushed out of the party because she and the WWCC refused to tow the party line.

| Huda and the Egyptian Feminist Union |

In the 1930s and 1940s, Huda started to turn her feminist work outwards, as she began framing feminism as not just an Egyptian issue but also a pan-Arab issue. In 1944, she helped found the Arab Feminist Union, but even before that, she worked to help feminist movements throughout the Middle East. When Palestinian feminists requested her help in 1943 she raised funds, and ended up starting the conference that would lead to the formation of the Arab Feminist Union.

Part of the reason Huda was so invested in framing feminism within a pan-Arab framework was because it was becoming rapidly clear that no real help was going to come from feminists in Europe, the United States, and Canada. While Western feminists meant well, and many certainly thought they were doing good, they looked down on Arab women, and failed to understand the differences between Arab and Western culture. White feminists viewed themselves as superior to Middle Eastern feminists because they were white, and colonial attitudes were still a prevalent feature at international feminist conferences. European feminists couldn't understand the struggle that Huda and other Middle Eastern feminists faced and therefore weren't reliable allies. Because she couldn't rely on the existing feminist organization's, Huda created her own.

Huda spent the latter years of her life lobbying and organizing. In the 1930s, her work started to focus on the rights of women workers and on ensuring that women were treated equally in the workplace. There were many instances when women workers came to Huda seeking help, and she dealt directly with the Egyptian Labor Board to resolve the issue.

In 1945, she was awarded the Nishan al-Karmal award, Egypt's feminine equivalent of a knighthood. She was, however, still unable to vote. She died two years later on August 12th.

Huda started the feminist movement in Egypt, and through her dogged work and determination, she was able to drastically improve the situation for women in Egypt. Though change was sometimes slow and incremental (the harem system would not be fully dismantled until after her death), she was able to put in place the infrastructure that would ensure that the next generation of Egyptian feminists was able to continue the fight after she was gone.

This article was edited by Mara Kellogg.

Sources

The Harem Years by Huda al-Shaarawi

"Early Twentieth-Century Middle Eastern Feminisms, Nationalisms, and Transnationalisms" by Mary Ann Fay

"Challenging Imperialism in International Women's Organizations, 1888-1945" by Leila J. Rupp

"Between Nationalism and Feminism: The Eastern Women's Congresses of 1930 and 1932" by Charlotte Webber

Huda Sharawi-Britannica

Huda Shaarawi-Encyclopedia

Shaarawi, Huda-Melissa Spatz